China's new 5-year plan brilliant news for mining

Image: Thierry Ehrmann

The end of China's one-child policy has grabbed all the headlines, but the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (to give its full designation) also outlined the direction of the world's second largest economy over the next five years.

China's 13th five-year plan running from 2016 - 2020 is the first one approved by Xi Jinping and was expected to focus on strengthening economic and market reforms first mooted in 2013.

Xi appointed himself head of a new "leading group on comprehensively deepening reforms" to overhaul China's investment-led economy into one driven by services and consumption two years ago.

The communique issued yesterday provides only the basic frameworks of programs and policies with a more detailed plan only made public in March.

But already it gives some indication that Xi and company, unnerved by slowing economic growth, may be throttling some of those free-market reforms to put their money again on investment to re-energize the sagging economy.

Wording from 2013 that mentions the establishment of "a unified, open competitive and orderly market system" which would play a "decisive role in allocating resources" is gone from the latest communique.For the next five years government plans to "encourage better allocation of resources" and the country will "prioritize quality and efficient development," but tellingly it's no longer (only) up to market forces to accomplish this.

Continuing to "raise consumption's contribution to growth" is still an important plank and there is also a promise that "government will intervene less in price formation," a clear reference to its botched stock market meddling earlier this year.

But Beijing's decision let urbanization happen at a faster pace and to stick to its target of "medium-high economic growth"and to double-down on a long-stated commitment to "double 2010 GDP by 2020" is the real kicker.

That 2020 GDP goal would require annual growth rates of 6.5% to go from a nominal $10 trillion last year to over $12 trillion in 2020. That's the equivalent of adding an economy the size of Switzerland's every year.

With the changes in messaging from 2013 the party leaders seem to suggest that such a Herculean task cannot be left to the market or services or consumption.

When growth inevitably begins to flag the Chinese government would likely respond like they always do: incentivize local governments to undertake large projects, mobilize state-owned enterprises for infrastructure investment and inject cash into the economy.

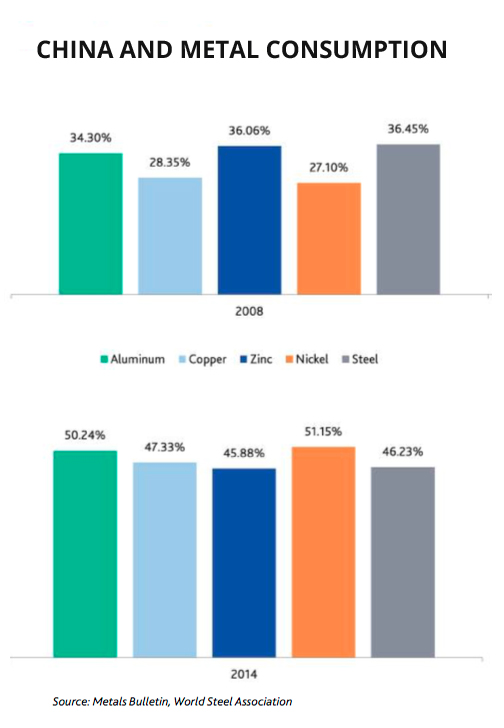

From already elevated levels in 2008, China's consumption of metals have only grown. What this chart will look like in 2020 is an open question and no-one is predicting another China-induced supercycle. But today's doom and gloom about China's supposed loss of appetite for commodities is certainly overblown too.

Source: Moody's