Amazon rainforest's riches up for grabs as Brazil to open indigenous reserves to mining

Brazil's new right-wing government, led by former army captain Jair Bolsonaro, is going ahead with announced changes to current mining regulations, which include a controversial plan to open up indigenous reserves to mining.

Most of the country's original population lives in the Amazon rainforest, which has an ecosystem seen by many as having worldwide ecological importance. Speaking at an event in Washington D.C., the country's Mines and Energy minister, Bento Albuquerque, acknowledged the environmental value of the vast area, but said it was also globally important because of the resources it holds.

"The Amazon is very important to the country. Not just in the respect of preserving the environment for the value it represents to the planet, but also in terms of its riches." - Mines and Energy minister Bento Albuquerque."The riches of the Amazon have to be explored in a rational and sustainable way that does not harm the environment," Albuquerque said Friday. "That effort shall also include the regulation of the use of indigenous and other areas."

Albuquerque said that mining was the sector his office needed to focus on. "It's the country's only industry totally privatized, except for the state-controlled exploitation of uranium, and the one that suffers the most with the delays in licensing, as it currently takes more than 20 years to obtain a permit," he added.

In an interview with Revistaforum, Brazil's deputy attorney general Carlos Bigonha said it would be almost impossible for the government to do what it wants, as mining in indigenous reserves is currently prohibited.

First, he said, it would need to hold consult with the affected communities. Next - assuming it gets the go-ahead from them - it would need to request the Congress' authorization, and then issue a supplementary law regulating exploitation in those lands.

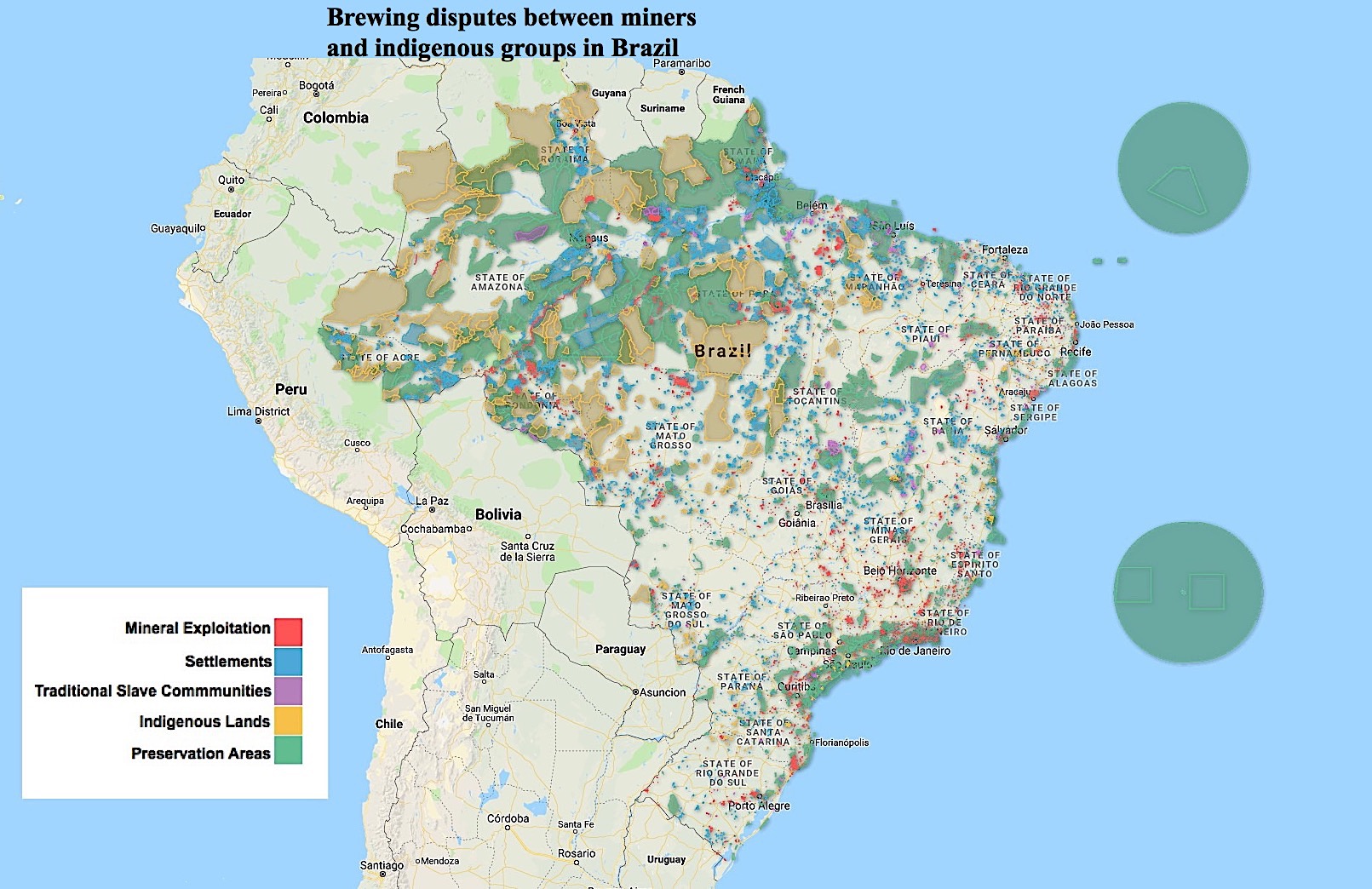

The government would also have to deal with over 400 brewing disputes involving mining companies, quilombos (communities made up of the ancestors of runaway slaves) and other indigenous peoples, according to Latentes, a journalistic project to map conflict areas in Brazil.

The team found that from the 428 potential conflicts detected in the country, 245 are found in reserves, while 183 involve traditional bondservant communities, as Brazil was the West's last nation to abolish slavery.

The mapping crosses data from Funai, the national indigenous affairs agency, the Palmares Foundation, which regulates quilombos, and data from active mining concession contracts signed by the newly reformed National Mining Agency.

Source: Latentes.

Bolsonaro's administration would face additional global and local scrutiny following a catastrophic mining accident at Vale's Corrego do Feij??o mine, which killed at least 300 people and polluted the surrounding areas.

With bodies still buried beneath the mud, public outrage is intense, and facilitating new mining endeavours is likely to cause some upheaval.

Climate scientists say opening up the Amazon for greater development could make it impossible for Latin America's largest nation to meet its reduced emissions targets in the coming years.

Other issues conservationists are worried about include Bolsonaro's criticism of the country's environmental agencies for blocking or taking too long to approve mining and energy projects. He has promised to reduce the wait time to license small hydroelectric plants to a maximum of three months, rather than the decade it can sometimes take.

Companies operating and exploring in Brazil are mainly after iron ore (the country is the world's top producer of the steel-making ingredient) and gold, though the nation also holds large reserves of bauxite, manganese and potash. It's also Latin America's No. 1 oil producer.