Cobalt price bulls' worst fears may just have been confirmed

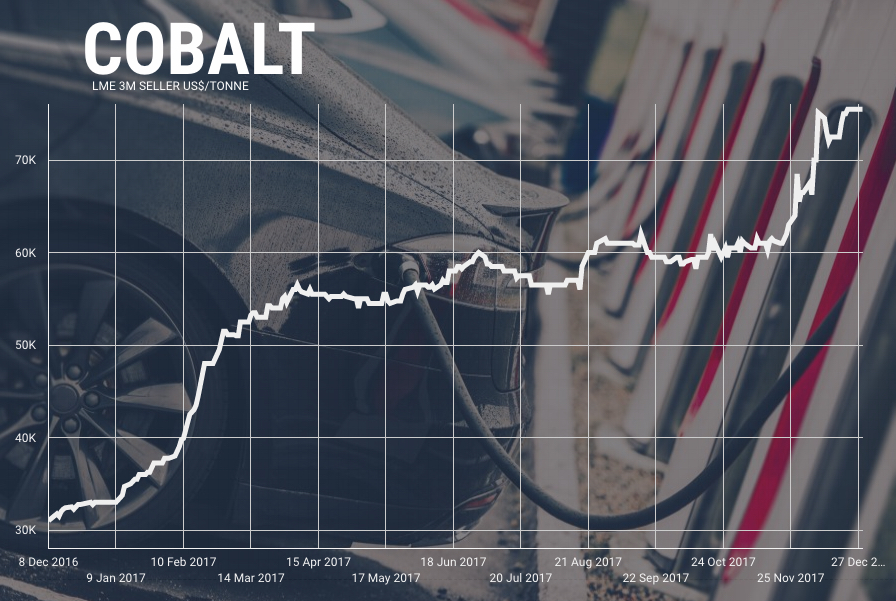

Cobalt prices went ballistic in 2017 with the metal quoted on the LME ending the year at $75,500, a 129% annual surge sparked by intensifying supply fears and an expected demand spike from battery markets. Measured from its record low hit in February 2016, the metal is more than $50,000 more expensive.

Cobalt prices went ballistic in 2017 with the metal quoted on the LME ending the year at $75,500, a 129% annual surge sparked by intensifying supply fears and an expected demand spike from battery markets. Measured from its record low hit in February 2016, the metal is more than $50,000 more expensive.

Given these lofty levels - and considering that the volatile commodity topped $100,000 a tonne a decade ago - battery makers and energy storage researchers have been working hard to find a substitute for cobalt, or at least reduce the required loading.

Now that breakthrough may just have been made.

Backed by the US Department of Energy, researchers at Northwestern University's McCormick School of Engineering led by professor of materials science and engineering Christopher Wolverton, have developed a lithium battery which replaces cobalt with iron (iron ore was priced at $76 a tonne on Thursday).

"That means that your phone could last eight times longer or your car could drive eight times farther"Northwestern in partnership with the Argonne National Laboratory created a rechargeable lithium-iron-oxide battery that's not only much cheaper but can also cycle more lithium ions than its common lithium-cobalt-oxide counterpart, technology that has been on the market for 20 years:

"Because there is only one lithium ion per one cobalt, that limits of how much charge can be stored. What's worse is that current batteries in your cell phone or laptop typically only use half of the lithium in the cathode."

The [Northwestern] fully rechargeable battery starts with four lithium ions, instead of one. The current reaction can reversibly exploit one of these lithium ions, significantly increasing the capacity beyond today's batteries. But the potential to cycle all four back and forth by using both iron and oxygen to drive the reaction is tantalizing.

"Four lithium ions for each metal - that would change everything," Wolverton said. "That means that your phone could last eight times longer or your car could drive eight times farther. If battery-powered cars can compete with or exceed gasoline-powered cars in terms of range and cost, that will change the world."

According to the institution's website Wolverton has filed a provisional patent for the battery and he and his team "plan to explore other compounds where this strategy could work."

Supply worries

Of course, the lab is a long way from the road but vehicle makers are spending tens of billions to push into into battery-powered vehicles and autonomous-driving systems.

Cobalt briquettes, Nikkelverk, Norway. Image: Glencore

While demand for lithium, copper, nickel and specialty metals will also increase with the global shift away from internal combustion engines to an electric vehicle market automakers have expressed the deepest concerns about the supply chain for cobalt.

Annual production of the raw material is only around 100,000 tonnes with the bulk coming from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where fears about political instability and the challenges of ethical sourcing combine to supercharge supply concerns.

According to S&P Global today six of the top 10 cobalt mines are in the DRC. Due primarily to Chinese investment by 2022 the central African nation will host the nine largest cobalt producers. Primary cobalt mines are scarce - 90% of global production is as a byproduct of copper and nickel mining.

In December luxury vehicle maker BMW said its needs for car-battery raw materials such as cobalt and lithium will grow 10-fold by 2025 and that it had been surprised at just how quickly demand is accelerating. Automakers including world number two Volkswagen have been scrambling to secure long term supply contracts, with little success.

Other players are also seeing opportunity in the cobalt market.

"It's a way for investors to speculate on the price of cobalt, plain and simple"Canada's Cobalt 27 Capital has been successful in raising additional funds to build its cobalt stockpiles since listing in June last year providing "a way for investors to speculate on the price of cobalt, plain and simple" according to the Toronto-based company's CEO. Reuters this week reported that just two firms apparently control at least 80% of cobalt stockpiles in LME warehouses around the world although the impact on the broader market could be limited given that inventories have dwindled to a mere 580 tonnes in another sign of how tight the market has become.

Top cobalt miner Glencore in December announced it's restarting production at its Katanga copper and cobalt mine in the DRC and recently commissioned a study to measure the impact of the booming EV and energy storage market would have on mining.

Based on an EV market share of less than 32% in 2030, forecast metal requirements are roughly 4.1m tonnes of additional copper (18% of 2016 supply). The move away from gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles would need 56% more nickel production or 1.1m tonnes compared to 2016 and 314,000 tonnes of cobalt, a fourfold increase from 2016 supply.

Katanga copper mine in Democratic Republic of the Congo. Image: Glencore