Copper smelter hits cause physical squeeze in Asia

The copper market is currently experiencing a squeeze on physical metal which is unexpected.

The London Metal Exchange (LME) price is treading water just above the $6,000 level, struggling to fend off bearish macro funds.

Mine supply is doing just fine with a conspicuous absence of disruption this year.

Yet, all the tell-tale signs of physical market tightness are there.

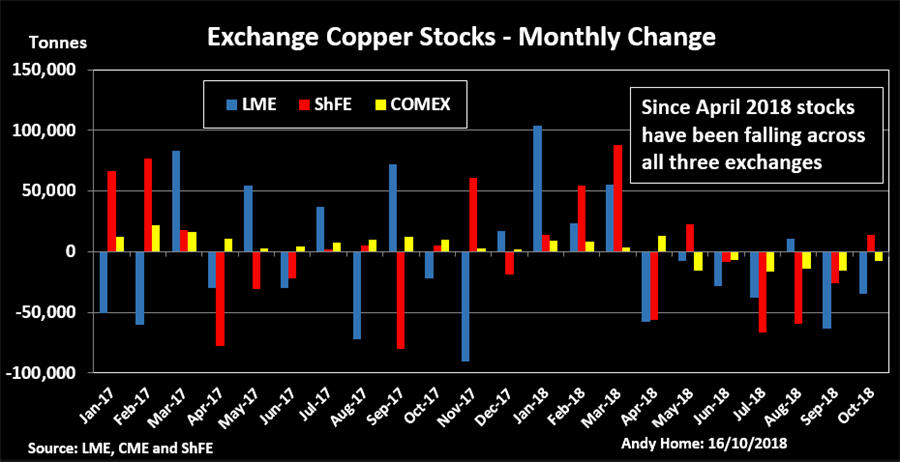

Global exchange stocks have been falling in near unison since April. Between them the London Metal Exchange (LME), COMEX and the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) hold 440,000 tonnes of copper, the lowest amount since June 2016.

Physical premiums are rising. The spot premium in Shanghai is $117.50 over the LME cash price. The last time it was above $100 was also in 2016.

Producers such as Chile's Codelco and Germany's Aurubis have announced hefty hikes in premiums to $98 and $96 respectively for European shipments next year.

And Chinese imports of refined copper are booming, up 16 percent in the first nine months.

Which is a clue that this scramble for physical copper is centred in Asia, where trade flows are adapting to a combination of smelter outages and changing scrap dynamics.

Graphic on global copper stocks, monthly changes:

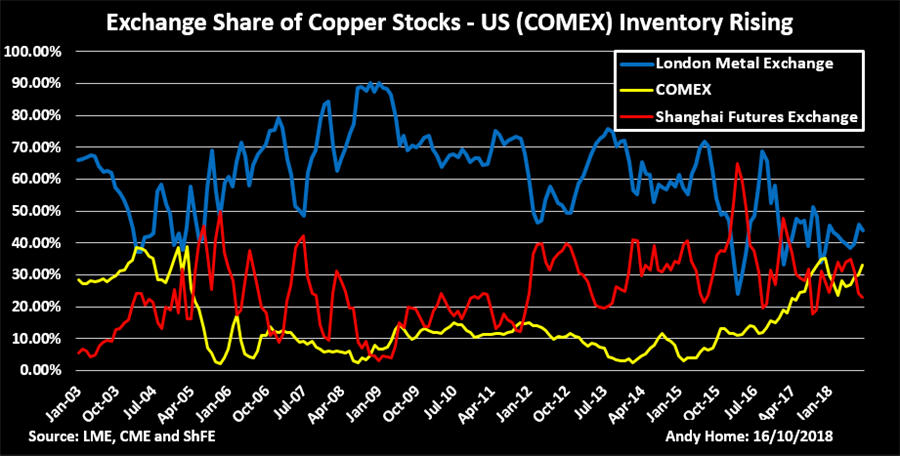

Graphic on global copper stocks by exchange:

Short of metal

The steady fall in headline exchange stocks has masked two underlying trends - the increasing amount of visible inventory in the United States and the sharp erosion of tonnage in Asia.

COMEX only operates domestic storage facilities but with just under 150,000 tonnes of registered metal it now holds more than the ShFE.

LME stocks, meanwhile, are highly concentrated in just two U.S. locations - New Orleans and Chicago. Between them they account for 71 percent of the 164,175-tonne total.

The amount of copper in the LME's Asian locations, by contrast, is only 21,025 tonnes, or an even more negligible 7,175 tonnes excluding the metal earmarked for physical load-out.

Shanghai exchange stocks have risen a little over the last couple of weeks but at 125,700 tonnes they are down heavily from their March peaks above 300,000 tonnes.

Asia, it seems, is running short of metal, which is why the Shanghai premium has nearly doubled in the space of three months.

Asian supply chains dislocated

The Asian component of the copper supply chain has been experiencing a high level of disruption.

Not at the mine stage of production, but rather at the smelter stage. This has caused significant shifts in the region's refined metal balance.

Vedanta Resources' Tuticorin smelter hasn't operated since March. Environmental protests turned violent in May and the local government has ordered a permanent closure.

Vedanta is appealing that decision but its only domestic production is now coming from the Silvassa refinery, which produced 15,000 tonnes in the third quarter.

Vedanta was supplying around one third of India's demand for refined copper, according to its website.

The country's resulting extra appetite for imports, however, has coincided with lower run rates at another key Asian supplier.

Glencore's Pasar smelter in the Philippines is undergoing repairs to its acid plant after a typhoon hit at the start of the year. Production was already down 13 percent year-on-year in the first six months.

Add China's own accelerated import activity to the mix and the rush to grab copper stocks in the Asian region starts to make sense.

The surge of refined metal into China, moreover, is itself down to another dislocation in the supply chain.

China's new restrictions on the purity of copper scrap imports have caused a drop in the flow of material from the rest of the world.

The effect was compounded in August with the imposition of 25 percent tariffs on scrap from the United States, which emerged at the start of the year as the number one supplier of higher-purity material.

In the rest of the world most copper scrap gets reintegrated into the supply chain at the semi-manufacturing stage. But in China most of it is used to make refined copper.

The country accounted for almost half the world's "secondary" refined production in 2017, according to the International Copper Study Group.

Scrap, in other words, feeds back into the refined metal balance very fast in China and this "scrap effect" is adding to the broader squeeze on availability in the region.

More dislocation to come

The copper market doesn't talk a lot about copper smelters. The supply narrative is always a mining one because how much comes out of the ground is still the key determinant of price, especially in copper with its long history of mine supply under-performance.

If smelters don't operate, on the other hand, the raw material will simply be refined somewhere else, ultimately not affecting the production-usage calculation.

It takes time, however, for flows to be restructured and it is the combination of hits to the smelting-refining part the production chain that is currently playing out in the Asian physical market.

And more dislocation is on its way.

Codelco has said it will close its Chuquicamata and Salvador smelters from Dec. 13 for 75 and 45 days respectively as it rushes to upgrade controls to meet new environmental laws.

However, as Barclays Research notes, "the Chuquicamata smelter processes complex copper ores that are high in deleterious elements, which not all smelters are able to treat." (LME Week Review," Oct. 12, 2018).

A possible consequence, it adds, is "that the copper cathode tightens further, even in the face of reasonable overall mine supply growth."

The appearance of more smelter bottle-necks will overlap with the potential for more upheaval in the copper scrap chain.

The Chinese authorities have threatened a total ban on metal imports next year.

No-one is believing them. The country imported 1.6 million tonnes of contained copper in scrap last year, according to research house CRU. It's simply too big a gap to fill without causing mayhem in the refined metal part of the supply chain. But Beijing's direction of travel is clear and ever tighter controls on scrap imports will keep suppressing volumes with a knock-on effect for Asia's refined copper balance.

This squeeze may have further to run.

(By Andy Home; Editing by David Evans)