Surprising Advantages Of Investing In Gold, A 50 Year Historical Analysis / Commodities / Gold & Silver 2019

One of the most common reasons to buygold is to use it as a stable store of value. This analysis uses 50years of history to test that common belief, and finds it woefully lacking - forit misses the best parts of investing in gold.

One of the most common reasons to buygold is to use it as a stable store of value. This analysis uses 50years of history to test that common belief, and finds it woefully lacking - forit misses the best parts of investing in gold.

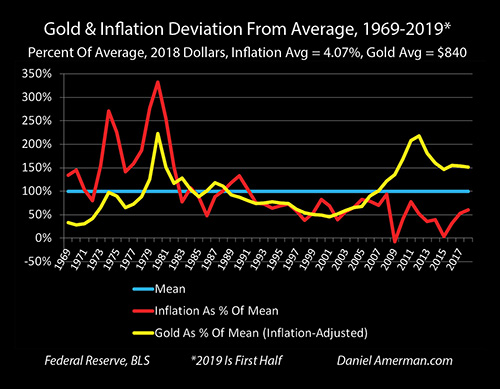

The graph below will be developed, andwe will show that gold is instead a more sophisticated (and desirable) investmentthan most people realize. When properly understood, gold can deliver uniqueadvantages to knowledgeable investors, and it can be put to much better usesthan just acting as a mere stable store of value.

As we will explore, the actual historyof gold is that it can deliver real (inflation-adjusted) profits that are up to7X greater than what perfect inflation hedge would deliver. When we look at thetimes that this wide outperformance occurs, this means that gold can have anintegral role in portfolio management in the modern era, and can "punchfar above its weight" when compared to such inflation hedge alternativesas TIPS.

This analysis is the 16thchapter in a free book. The earlier chapters are of essential importance forachieving full understanding, and an overview of some key chapters is linkedhere.

Level One: The Theory Of Gold As Stable Money

The most popular perception of gold isthat it acts as a stable store of value, and that it will protect the purchasing power of savings againstthe ravages of inflation.

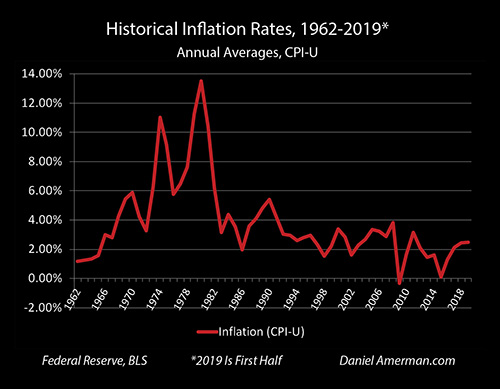

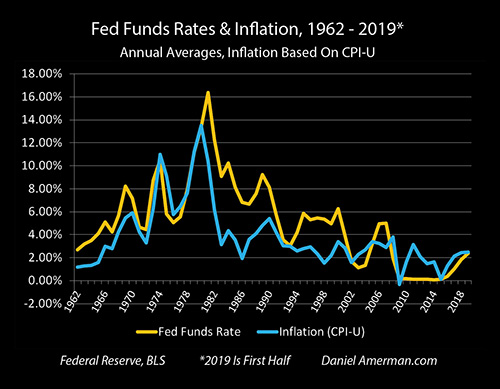

The need for such protection can beseen in the graph of inflation above, which shows average annual rates ofinflation in the United States for the years 1962 through the first half of 2019.Any time the red line is above 0%, then the value of the dollar is falling.While the rates of inflation varied widely, on an annual average basis thedollar lost value every single year with the exception of a miniscule increasein value in the year 2009, during and in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

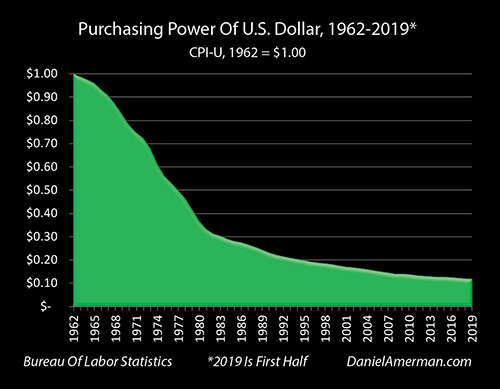

The cumulative impact of this steadydestruction of the purchasing power of the dollar can be seen in the graphabove. When compared to what it would buy in 1962, the dollar would only buy 50cents by the year 1977. The purchasing power of the dollar would then drop inhalf again by the year 1989, and then in half again - down to a value of 12cents on the dollar - by the year 2017. (If we go back to the 1933 when FDRtook the U.S. off of the gold standard for domestic purposes, the paper dollarhas lost 95% of its value since that time.)

The actual purchasing power of a vastamount of saver wealth has been steadily destroyed over the decades - and thetheory behind owning gold it that it is supposed to keep that from happening.How has that worked in practice?

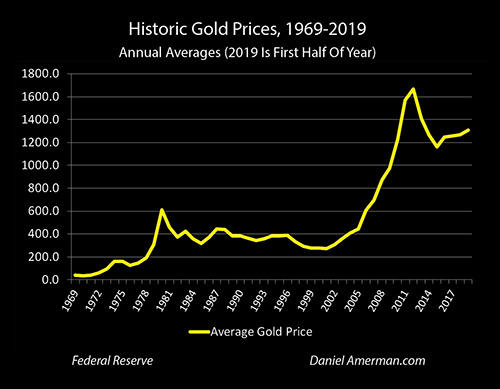

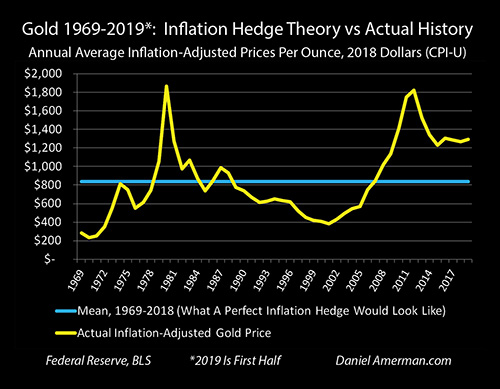

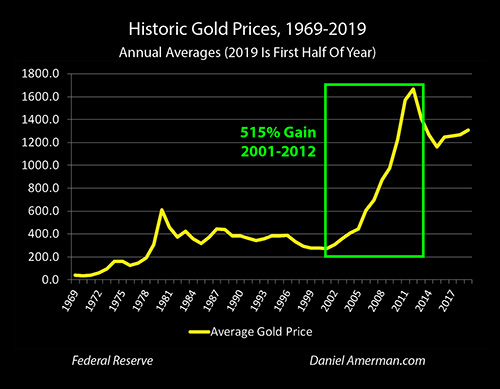

The graph above shows average annualgold prices from 1969 to the first half of 2019 - and gold has done very wellindeed over those years. The average price of gold was $41 per ounce (on theLondon exchange) in the year 1969, and it was up to $1,307 dollars an ounce bythe first half of 2019.

So the value of each dollar was waydown, the number of dollars that each ounce of gold could buy was way up - did goldeffectively protect the purchasing power of savings as it was supposed to?

Testing Gold As An Inflation Hedge

To test whether gold was an effectiveinflation hedge, we need to look at the value of gold over time ininflation-adjusted terms.

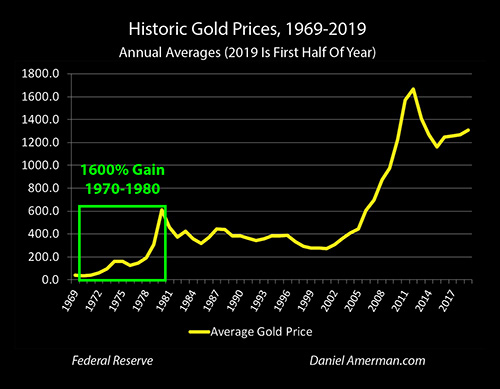

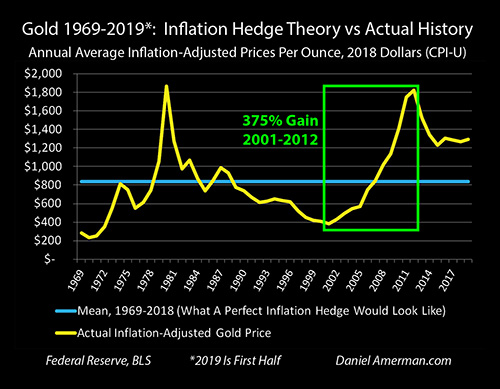

When we adjust the average annualprice for an ounce of gold by the purchasing power of the dollar in each year,we get the graph above.

A hedge is something that protects thevalue of a financial position. A perfect inflation hedge that fully protectssaver purchasing power would necessarily be a flat line in inflation-adjustedterms - an ounce of gold would always have the same real purchasing power,regardless of the rate of inflation that is experienced.

An example of such a perfect hedge isthe blue line above. The average inflation-adjusted price of an ounce of goldbetween 1969 and 2018 was $840 an ounce (in 2018 dollars). If gold were actingas a perfect inflation hedge, then exactly maintaining purchasing power would meansticking to the very stable and boring blue line above, with little or noannual variation.

However, when we look at the yellowline of actual historical gold prices on an inflation-adjusted basis - we getwild fluctuations instead of boring stability. The real purchasing power ofgold soars, and then plunges, and then soars, and then plunges.

Let's break it apart, and see if wecan get a better idea of what is happening.

The 1970s were a time of inflation,and on an annual average basis, the price of gold jumped from $36 an ounce in1970, to $613 an ounce in 1980, which was a gain of about 1600% in ten years.

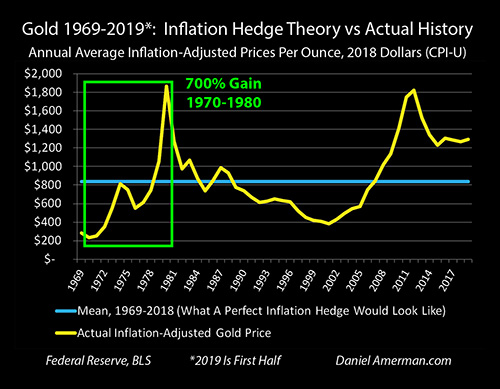

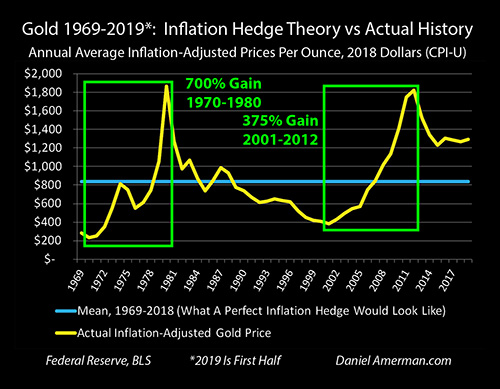

When we adjust the prices forinflation and put them in more current terms (2018 dollars), then the price ofgold moved from $232 an ounce in 1970, up to $1,869 an ounce in 1980, which wasa gain of about 700% in ten years.

Now, if gold were acting as a perfectinflation hedge or stable store of value, it should have started at aninflation-adjusted value of $232 an ounce, and ended at an inflation-adjustedvalue of $232 an ounce.

Instead, gold experienced aspectacular 8X increase in value in inflation-adjusted terms, creating thetowering spike seen above. For gold investors - this movement was lucrative,and far more profitable than if gold were merely just keeping pace withinflation. (Just to be clear: going from 100% to 800% is an 8X increase but again of 700%, just as doubling (2X) the price of an investment produces a 100%gain.)

That said, there is a price that goesalong with those extraordinary gains - and that is accepting that theoverwhelming majority of the gains did not come from gold acting as a stablestore of value, but quite the reverse. This then set the stage for a much moreunpleasant era for gold investors.

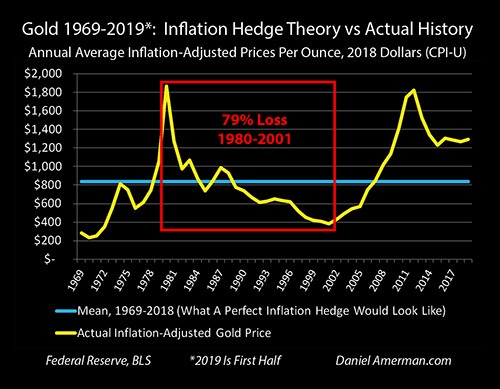

After the peak annual average price of $613 an ounce in 1980 (not adjusting forinflation), the price of gold would trend downwards for the next 21 years,bottoming out at $271 an ounce in the year 2001.

That was a 56% loss on its own, butthere was another problem as well. Inflation had not stopped, indeed some ofthe peak years for inflation in the modern era occurred during that time, witha 10.4% rate of inflation in 1981, and a 6.2% rate of inflation in 1982. By2001 - the dollar had lost 53% of its purchasing power, relative to what itwould have bought in 1980.

In order to just keep up withinflation, to act as an inflation hedge or stable store of value, gold shouldhave more than doubled in price between 1980 and 2001 - but in practice itdropped in price by more than half.

When we combine the much fewer numberof dollars that each ounce of gold could buy, with the much lower value of eachof those dollars, then we get the graph above. In inflation-adjusted terms(2018 dollars), the value of gold fell from $1,869 an ounce in 1980 down to$384, which was a 79% decrease in purchasing power.

If someone had just held a dollar,their purchasing power would have been down to 44 cents by 2001. However, ifthey had held gold in order to protect themselves from inflation - then theirpurchasing power would have been down to 21 cents by 2001. Savers would havebeen much better off just holding on to their paper dollars.

What actual financial history shows usis that gold completely failed in its job of acting as a stable store of valuefor a period of a little more than two decades, losing almost 80% of itsinflation-adjusted purchasing power.

Now, I'm not saying this to knock goldor to offend anyone. Indeed, the place that I am going is that gold is a farbetter investment than if it were just a mere stable store of value or perfect inflationhedge. Particularly from an overall portfolio perspective in these days of heavy-handedcentral banking interventions, including quantitative easing and many negativeinterest rates around the world - gold is a more sophisticated and powerfulfinancial tool than most people realize.

But to uncover that real value, weneed to look with both eyes wide open, and see gold for what it truly is,rather than what many people want it to be. In the real world, gold was awfulas an inflation hedge for two decades. That historical fact then in turn setthe stage for gold to again spectacularly outperform what a mere stable storeof value could do.

From the bottom point of an annualaverage price of $271 an ounce in 2001, gold would soar to an average price of$1,669 in the year 2012. This increase in price would produce a 515% gain overa period of 11 years.

Even when we adjust for inflation -there was still a stunning gain. Gold went from $384 an ounce in 2001 (2018dollars), to an annual average price of $1,825 an ounce in 2012. This was again of 375% over the eleven years, even after fully discounting for thedecreased purchasing power of the dollar.

To briefly review, using the graphabove which is focused on the positive: 1) gold performed spectacularly duringthe ten years from 1970 to 1980, with a gain that was 700% better than what canbe explained by merely keeping up with inflation; and 2) gold also performedextremely well during the eleven years from 2001 to 2012, with a gain of 375%even after fully taking inflation into account.

Those two add up to 21 years of bullmarkets. However, the gap between the two spectacular bull markets was dominatedby 21 year bear market, where gold failed miserably in its job of being aninflation hedge, losing 79% of its purchasing power.

I think we can safely draw twoconclusions from this review so far. The first is that there is something goingon that is not just about keeping up with inflation or gold acting as a stablestore of value. The second conclusion is that whatever is actually happening -it isn't boring.

In the attempt to find a betterexplanation - let's raise the sophistication of our analysis by a notch.

Level Two: Gold As An Investment Subject To Supply & Demand

Let's say that gold is not money (atthis point in history), but that it is an investment. Of course, once we adoptan investment framework, then we have to take into account that investmentschange in price depending on supply and demand.

If we look at gold in supply anddemand terms, then many other factors come into play. We have supply in termsof the physical production of gold from mines, or from central banking salesfrom their reserves. We have demand for gold for such things as jewelry orcentral banks increasing their gold reserves, with either use pulling the goldout of circulation. We also have the demand for gold in other nations changingthe price for gold in their currencies, and then we need to consider how thechanging value of the dollar intersects with that changing demand for gold inother countries.

For simplification, we will ignorethose factors for now, and concentrate on one basic relationship within theUnited States.

If most people view gold as a way ofprotecting themselves - or profiting - from inflation, then the higher thatinflation goes, the higher the price of gold should go. More people are comingin with their money, trying to buy gold. Because demand is rising sharply atthat point - prices should be rising sharply as well, even after discountingfor inflation.

In addition, rising markets tend todraw in more money. The increasing demand for gold as an inflation hedge shouldbring in money from speculators as well, who see the rapidly rising prices andwant to participate. This further increases demand, which would furtherincrease prices.

Conversely, if people begin to losetheir fears about inflation - then the demand for gold should drop sharply, sothere is no longer the upward price pressure. Now the supply of people wantingto exit gold exceeds the demand from new investors who are worried about risinginflation - so prices should be dropping. Falling prices send the speculatorsheading for the exits, which further increases the excess supply problem, andthat should decrease prices even more.

So if gold is an investment wheredemand increases with rising inflation, and demand falls with decreasinginflation - then we should be able to see that relationship over time.

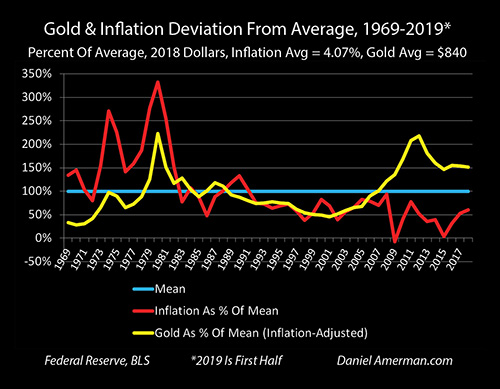

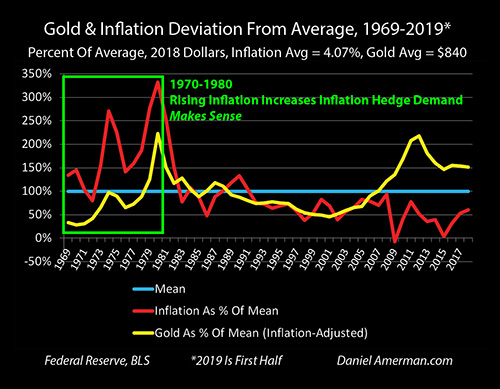

To put both inflation and gold on thesame graph, I averaged each for the years 1969 to 2018, and determined that theaverage annual rate of inflation was 4.07%, while the average inflation-adjustedprice of gold was $840 an ounce. These averages are expressed in percentageterms, with the average (mean) being the 100% blue line for both inflation andgold.

When inflation was above average - thered line goes above the blue line. When inflation-adjusted gold prices go aboveaverage - then the yellow line goes above the blue line.

Now let's revisit the 1970 to 1980gold bull market, looking at both the rate of inflation and at what washappening with inflation-adjusted gold prices.

The rate of inflation was belowaverage in 1972, and so were gold prices. Then the rate of inflation shotupwards in 1973 and 1974 - and inflation-adjusted gold prices spiked upwardsright along with it, as more investors sought protection from inflation.

Annual rates of inflation fell back quitea bit in 1975 and 1976 - and so too did the inflation-adjusted price for goldas fewer investors sought out inflation protection.

There was then a tremendous spike in therate of inflation over the next four years, with average annual inflationreaching 13.5% in 1980. As shown on the graph, this was equal to 332% of ourlong term average rate of inflation of 4.07%.

Demand soared for protection frominflation, sending gold prices upwards at a rate that was far in excess of thehigh rate of inflation, the surging prices drew in speculators, which thenfurther increased real prices for gold, and gold topped out at aninflation-adjusted price of $1,869 an ounce, which as shown on the graph, wasequal to 223% of the long term average price of $840 an ounce.

The relationship is not quite perfect- but the yellow and red lines seem to have a very strong visual correlation,with upward spikes in the rate of inflation producing upwards spikes ininflation-adjusted gold prices (as demand rises), and downward spikes ininflation producing corresponding downward spikes in inflation-adjusted goldprices (as demand falls).

When we look at the changes in goldprices from this viewpoint - then the three phases of the first spike up, the spikedown, and then the final soaring spike up, all just plain make sense. There isa great deal of explanatory power.

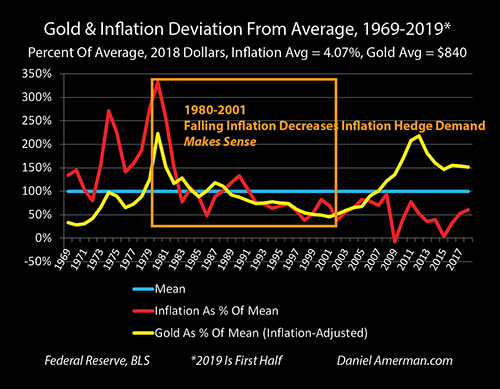

Now, let's take a look at the periodfrom 1980 to 2001, using the same visual tool. On a year by year basis, therelationship is not quite as tight - but from big a picture perspective, itremains remarkably good.

Annual rates of inflation andinflation-adjusted gold prices plunge together from 1980 to 1982, continuingthe close relationship that we saw from 1972 through 1980. This is exactly whatwe should expect - a plunging rate of inflation should create a plunginginvestor demand for protection from inflation, this should be exacerbated bythe flight of speculators from the market, and the end result should be adramatic plunge in inflation-adjusted gold prices.

For the 1983 through 1990 period, theyear by year correspondence is not as good as the remarkable similarity that wesaw from 1972 through 1982 - but the range is very similar. Inflation andinflation-adjusted gold prices are each oscillating up and down in a relativelylimited range over and above their averages.

Indeed, when we average inflationbetween 1983 and 1990, it was equal to 95% of its long term average, andinflation-adjusted gold prices in that period were equal to 103% of their longterm average. Close to average rates of inflation should produce close to averageinvestor demand for protection from inflation, this should produce close toaverage inflation-adjusted gold prices - and that is what we got.

During the 1991 to 2001 period, both ratesof inflation and inflation-adjusted gold prices were consistently below theirlong term averages. The visual correlation now returns to being remarkablyclose - indeed, almost perfect - for the years 1991 to 1999, before inflationseparated itself with a distinct red spike upwards in 2000 and 2001.

However, inflation never did reachaverage, and the spike was fairly small in comparison to previous spikes. Whenwe average the full 1991 to 2001 period, then inflation was equal to 69% of itslong term average, and inflation-adjusted gold prices were equal to 65% oftheir long term average. That is aremarkably close correspondence, and it makes perfect sense. Rates ofinflation that are well below average should produce a demand for investmentsthat protect from inflation that is well below average, and that shouldlogically lead to inflation-adjusted gold prices that are well below average.As it did.

For the whole period between 1980 and2001 - the relationship between inflation-adjusted gold prices and the changingrate of inflation just plain made sense.

Gold As A Uniquely Valuable Investment Category

When we test the theory of gold as astable store of value and perfect inflation hedge - then none of what actuallyhappened between the early 1970s and early 2000s makes any sense. The wildspikes up in the purchasing power of gold shouldn't have happened, and thesharp spikes down shouldn't have happened either. Gold never should haveexperienced a 700% gain in inflation-adjusted terms over a decade, and it nevershould have lost 79% of its purchasing power over a more than two decade periodeither.

The actual history invalidates thebelief system. (At least for those years, it is different over the longer term ofprevious centuries when gold was actually serving as money, rather than as anescape hatch for investors who were fleeing the destruction of the purchasingpower of fiat money).

However, when we look at gold as a popularinvestment category dominated by the laws of supply and demand, whereincreasing demand increases values as inflationary fears rise, and decreasingdemand drives values down when inflationary fears fall - then everything makessense.

This does not invalidate theattractiveness or desirability of gold as an investment for protecting againstinflation. Instead, gold becomes a substantially more sophisticated andattractive investment, particularly when viewed from a portfolio perspective.

As an example, let's say that someonekeeps 10% of the value of their portfolio in gold, and the other 90% is moneyor investments that are vulnerable to the ravages of inflation. If gold is astable store of value, and inflation rises sharply - then 10% of the portfoliokeeps up with inflation, the other 90% does not, the purchasing power getsravaged, and the investor is left with a 90% exposure to inflation on aportfolio basis.

However, If gold is not only justkeeping up with inflation, but can dramatically rise in value ininflation-adjusted terms when inflation spikes upwards, then at the very timethat the investor needs it most - gold can produce excess gains that can equal100%, or 300% or even 700% of the original investment amount. In this casethese extraordinary gains can reach out and shelter the inflation losses in therest of the portfolio. Depending the specifics, most of the inflation-basedlosses in the other 90% could be covered - or the investor might be kept whole,or could even come out ahead (at least in pre-tax terms).

This ability for a relatively small portfoliocomponent to "punch above its weight" and potentially reach out andshield a much larger portfolio from inflationary losses is both rare andextremely valuable. This is somethingthat can't be done with a mere "stable store of value", and it alsocan't be done with inflation protection alternatives such as TIPS.

Of course, conversely, if inflationdoesn't materialize, then our more sophisticated view of gold pricing makes itplain that the investors could lose most of the purchasing power of theirinvestment over time. This might seem a problem in isolation (and it is a bigproblem if gold is most of the portfolio), but so long as precious metals are aminority component, then from an overall portfolio perspective the response tothis potential issue could be - so what?

The other 90% is doing just fine. Thegains generated during a sustained period of prosperity and low inflation wouldlikely dwarf the slow incremental losses of the 10% component (in this example)that is invested in gold.

This supports a more sophisticatedview of gold as a unique and highly attractive form of portfolio insurance.When the insurance turns out not be needed, then as with any insurance there isan ongoing cost in terms of slow losses, or the opportunity cost in terms of foregonecash flows and capital gains from other investment categories. However, whenthe insurance is needed during times of sharply rising inflation - thehistorical track record shows that gold delivers, and in amounts that cangreatly exceed what is produced by some other types of inflation hedges.

While beyond the scope of thisparticular analysis, there a number of other unique advantages to gold whencompared to many other financial instruments. The first and perhaps mostimportant being that it isn't an actual "financial instrument", butis instead a physical asset, a yellow metal that is very valuable in smallquantities and is quite portable.

Now, the difference between having allof one's assets in (effectively) electronic form and dependent on the stabilityof the global financial system, versus having some level of reserves that arenot in electronic form nor part of the financial system may seem trivial orunimportant to most, and that is what it will be, quite unimportant - until itisn't.

(To be clear, the 10% number is justan example and not a suggestion. It is not uncommon to recommend a 5% to 10%precious metals weighting for high net worth investors - just in case - even ifthis is less common with many smaller investors. What is appropriate for anygiven individual, and whether that level is 5% or 25%+, is entirely dependenton the beliefs and circumstances of that individual.)

A Break In The Pattern

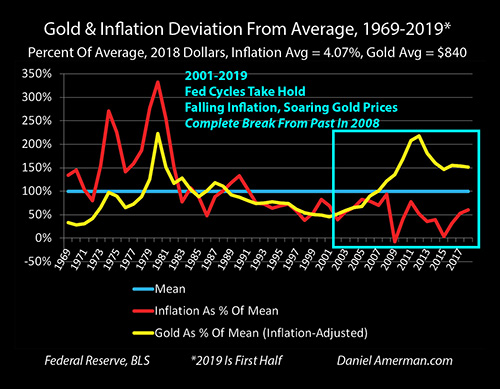

While what we have been reviewingworked great for many years, there is an issue, and it is plainly visible onthe right side of the graph below.

As is visually obvious, therelationship between inflation-adjusted gold prices and annual rates ofinflation completely broke down after 2008. In the aftermath of the FinancialCrisis of 2008, the average annual rate of inflation fell to 38% of its longterm average. Based upon what we saw over the previous three decades, then goldshould have fallen to an inflation-adjusted average price equal to somethingroughly around 38% of $840, which would be an inflation-adjusted price of about$319 an ounce (in 2018 dollars).

Gold didn't fall to $319 an ounce, butdid the direct opposite. If we look at the average inflation-adjusted price forgold between 2009 and 2018, it was equal to $1,408 an ounce, which is equal to168% of the long term average. This meansthat the average price of gold was 4.4X greater than what history indicates itshould have been, based upon the government reported rate of inflation (168% /38% = 4.4).

(Whether the government reported rate ofinflation is accurate is an analysis for another day.)

This is a "feature", not aproblem. The extraordinary divergence between the red line and gold line after2008 is indeed boldly obvious. The numbers are very clear as well.

An extraordinary breakout has occurred- and the breakout is to the upside.

Something has changed - and it isincreasing the demand for gold far above what it should be just based uponsolely the government-reported rate of inflation.

It is also worth noting that thestarting value for gold was $41 an ounce in 1969, and $36 an ounce in 1970.These numbers are much more reflective of gold prices in prior decades, whengold prices were pegged to the dollar for currency exchange purposes via theBretton Woods agreement. The inflation-adjusted value of $41 an ounce for goldin 1969 is equal to $281 today (or at least based on the 2018 average value ofthe dollar).

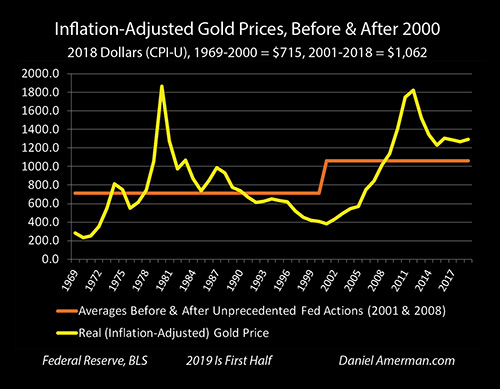

Another alternative is to take thesame approach as we have been taking for other asset classes in previouschapters, and compare the average inflation-adjusted value of gold from 1969 to2001, to average prices from 2000 to 2018. The previous long term average pricefor gold when we do not include the post-2000 prices is $715 an ounce.

So whether we look at simple historicaverages for inflation-adjusted gold prices, or we look at norms in the decadesprior to the early 1970s, or we look at what was developed herein in terms ofthe previous close relationship between rates of inflation andinflation-adjusted gold prices - from any of those perspectives, the currentinflation-adjusted value of gold is abnormally high from a historicalperspective.

Now, it needs to be noted that none ofthis necessarily negates the future relationship between rates of inflation andinflation-adjusted gold prices. All else being equal, an increase in inflationshould increase the demand for gold as protection from inflation, the higherthose prices go as a result, then the more speculators that should be drawn in,and there is every reason to believe that gold prices would again increase at arate well in excess of the rate of inflation. So the advantages of using goldas a portfolio hedge against inflation should remain, and they should still bequite powerful.

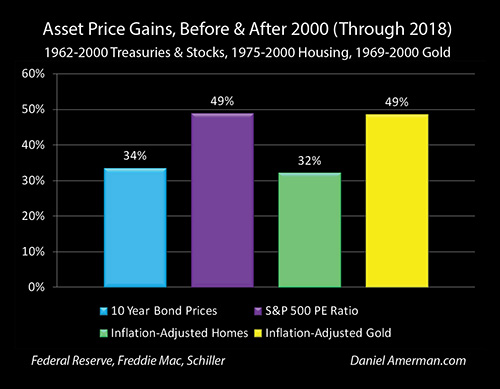

This is the sixteenth chapter in thisbook that is in the process of being written, and we have previously beenexploring the three bars on the left, those of the much higher asset prices thatwe have been seeing for bond prices, home prices and the stock value that isbeing assigned for each dollar of corporate earnings.

The yellow bar on the right shows a49% increase in the inflation-adjusted price for gold from 2001 to 2018,relative to the 1969 to 2000 period. (Which is different from the 1969 to 2018averaging mostly used in this particular analysis.)

As with each of the other assetcategories, gold is up sharply, and it indeed equals the maximum increase forthe other categories, that of the 49% increase in PE ratios for the S&P500. But the source of gains for gold is entirely different than with the otherthree categories.

As we have been exploring, we havebeen going through cycles of crisis and the containment of crisis, with evermore heavy-handed Federal Reserve interventions eventually leading to everyhigher asset prices across all the major investment categories.

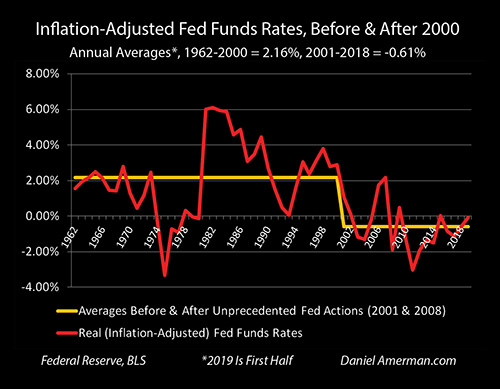

Using zero percent interest ratepolicies and quantitative easing in combination, the Fed has completely distortedthe investment markets. Yes, inflation was falling as can be seen above, butthe Fed was forcing down interest rates even more.

In combination, this produced thebizarre anomaly explored in previous chapters, where the Federal Reserve forcednegative interest rates on the United States as a whole (in inflation-adjustedterms), for a period of eighteen years. It was that distortion which ultimatelycreated elevated asset values for stocks, bonds and real estate.

That very same distortion should have drivengold prices to near historic lows, if inflation rates were all that determinedgold prices - but it didn't. Instead we see what is arguably the greatestinvestment price distortions for any asset category - perhaps as much as 4.4Xhigher than what the rate of inflation alone would indicate - and it is comingfrom the direct opposite source of the higher asset valuations for stocks,bonds and real estate.

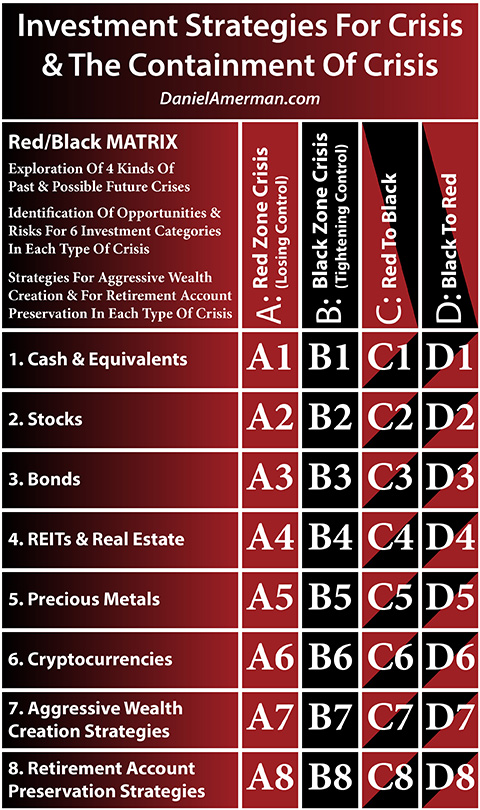

The graphic above is the framework wehave been developing for exploring the new cycles of crisis and the containmentof crisis (an introduction to the Red/Black matrix is linked here.)

For this book, this is our first closelook at the fifth row, that of precious metals. Because it is so different fromthe other rows, it can do some fascinating things, particularly when viewedfrom within an overall portfolio context.

We've reached the limits for a singlechapter here, and further development will take another chapter. I hope that thischapter has been of interest to you in terms of seeing precious metalsinvestment in a different light, as well as identifying what has been sodifferent in recent years.

Advantages Of Investing In Gold, A 50 Year Historical Analysis

Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Website: http://danielamerman.com/

E-mail: mail@the-great-retirement-experiment.com

Daniel R. Amerman, Chartered Financial Analyst with MBA and BSBA degrees in finance, is a former investment banker who developed sophisticated new financial products for institutional investors (in the 1980s), and was the author of McGraw-Hill's lead reference book on mortgage derivatives in the mid-1990s. An outspoken critic of the conventional wisdom about long-term investing and retirement planning, Mr. Amerman has spent more than a decade creating a radically different set of individual investor solutions designed to prosper in an environment of economic turmoil, broken government promises, repressive government taxation and collapsing conventional retirement portfolios

© 2019 Copyright Dan Amerman - All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: This article contains the ideas and opinions of the author. It is a conceptual exploration of financial and general economic principles. As with any financial discussion of the future, there cannot be any absolute certainty. What this article does not contain is specific investment, legal, tax or any other form of professional advice. If specific advice is needed, it should be sought from an appropriate professional. Any liability, responsibility or warranty for the results of the application of principles contained in the article, website, readings, videos, DVDs, books and related materials, either directly or indirectly, are expressly disclaimed by the author.

© 2005-2019 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.