Uranium price: best performer of 2018 set for more gains

The rally in uranium prices, which began in April this year amid production cutbacks in Kazakhstan and Canada, is set to continue as inventories of the nuclear material decline for the first time in nearly a decade.

Production at Kazakhstan state-owned uranium miner Kazatomprom, responsible for more than a quarter of global output, was 19,600 tonnes during the first eleven months of 2018, a 7% decline compared to the same period in 2017. Top listed uranium producer Cameco suspended production at its McArthur River operation in Saskatchewan a year ago, but in July the company announced an indefinite shutdown of the mine, which can produce more than 11,000 tonnes of U3O8 (yellowcake) although actual production never came close to nameplate capacity.

This tipping point is hard to predict, but could occur soon given the rapid decline in uranium output and the difficulty of securing future offtake agreements at current pricesStruggling French nuclear giant Areva (rebranded as Orano this year) slashed production more than a year ago. In August Paladin put its Langer Heinrich mine in Namibia on care and maintenance, although this week the Sydney-based miner said it's working on a possible restart of operations with vanadium as a byproduct (vanadium is trading at record highs and the only metal outperforming uranium).

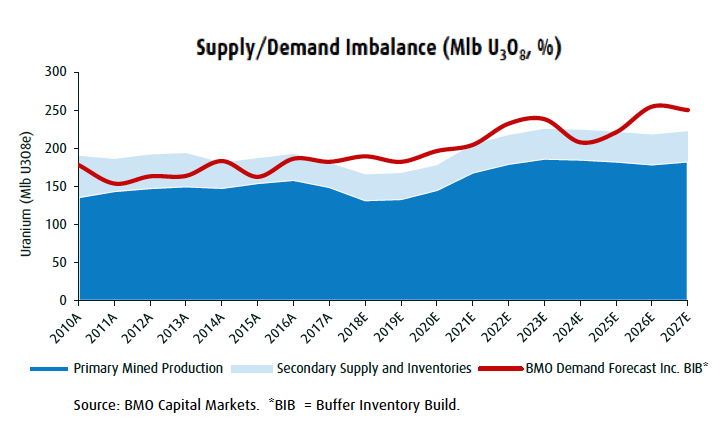

In a research note on Kazatomprom, BMO Capital Markets says the production discipline from top miners will break the trend of rising global uranium inventories following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011 and prompt the first production deficit in more than a decade.

The net result is that uranium has entered a period of structural undersupply and we forecast the beginnings of inventory drawdown, which should continue to provide upward bias to the uranium price as we exit the year.

Inventories can be divided into two broad categories; strategic and excess inventories, with the definition of each somewhat subjective. If utilities begin to worry about the security of future supplies then excess inventories can quickly be reclassified as strategic, leading to a shift in purchasing strategies.

This tipping point is hard to predict, but could occur soon given the rapid decline in uranium output and the difficulty of securing future offtake agreements at current prices.

Source: Having Your Yellowcake and Eating It. BMO Capital Markets November 2018

BMO analyst Alexander Pearce says Chinese nuclear plans are core to the uranium outlook, and he anticipates that Beijing will recommit to its longer term nuclear targets at the upcoming plenary session of the ruling communist party, where economic goals for the next five years are set.

China has 42 operating nuclear reactors, 16 reactors under construction and a further 43 planned. At the end of November, the country's national uranium corporation bought control of the Rossing uranium mine in Namibia. China is also behind the only sizeable uranium mine to come into production in the past few years, the Husab mine in Namibia, although ramp there has been slow.

The spot uranium price jumped to just shy of $30 a pound last week, up more than 20% since the start of the year. Today's price also compares to an all-time high of nearly $140 a pound reached in June 2007. BMO predicts a gradual increase in the uranium price as inventories are reduced and a long-term incentive price of $55 per pound, nominally in 2023.