Uranium supply crunch may be just around the corner - experts

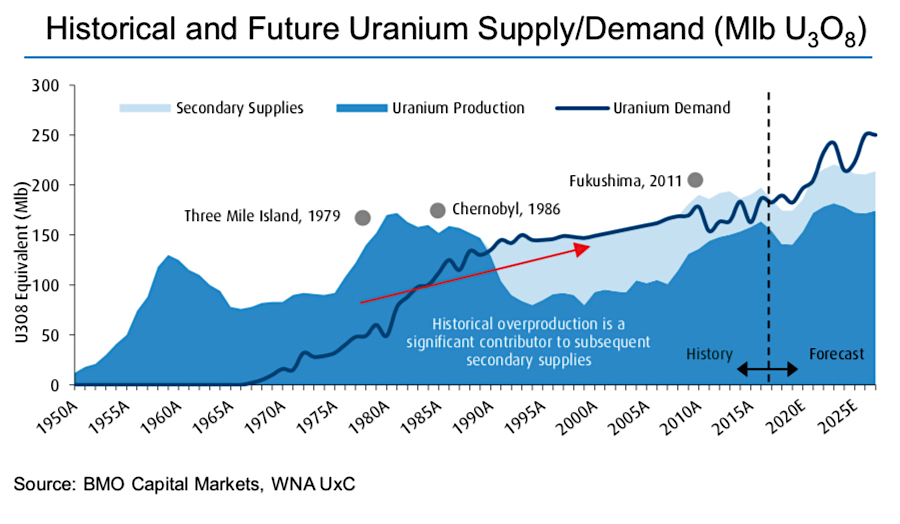

Production cuts, halted projects and operations, as well as renewed interest from investors has helped drive uranium prices up by 30% in the past four months, but experts remain cautious about the long-term outlook for the commodity.

Decade-low prices have had a negative effect on the profitability of existing mines and a devastating effect on the capacity of early-stage projects to raise the necessary funding to be mine-ready when demand picks up.

"The overall nuclear fuel chain remains a challenging environment, with low prices across the chain weighing on margins for producers and consumers," BMO analysts Colin Hamilton and Alexander Pearce said in a seminar part of the World Nuclear Association's (WNA) Symposium, which kicked off in London on Wednesday.

Taken from: BMO's U-Turn: Uranium Thematic Seminar.

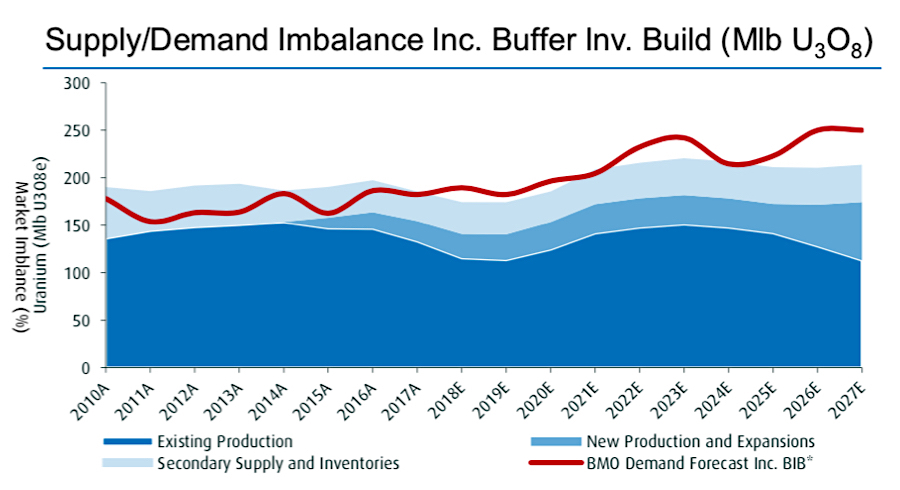

They noted, however, that recent supply cutbacks by major producers - mainly Canada's Cameco (TSX:CCO) (NYSE:CCJ) and Kazakhstan's state-owned miner Kazatomprom -, as well as the closure of a number of higher-cost mines, are starting to shift the balance into a deficit for the first time in more than a decade.

Cameco, the world's largest publicly traded uranium producer, has indefinitely suspended key operations and reduced its workforce across all sites, including its head office.

Kazatomprom, in turn, not only lowered output, but also recently bypassed the spot market by selling a big portion of its annual output production to Yellow Cake, a London-listed investment vehicle planning to buy and store large amounts of the metal in anticipation of higher prices.

Taken from: BMO's U-Turn: Uranium Thematic Seminar.

The entrance of new buyers such as Yellow Cake and hedge funds could make the supply shortage even more steep, BMO's Hamilton said.

The key, he added, would be to determine how much of the currently excessive inventory levels are actually available to the market.

BMO estimates global inventories have increased from 598mlb of uranium in 2009 to almost 800mlb, or about four years of demand. However, it doesn't have a rough guess of how much of that stock is uncommitted and available to trade.

While he still sees inventories as an overhang for uranium, the recent market events show the supply side of the industry is beginning to address issues that have led to consistent inventory build over the past decade.

Taken from: BMO's U-Turn: Uranium Thematic Seminar.)

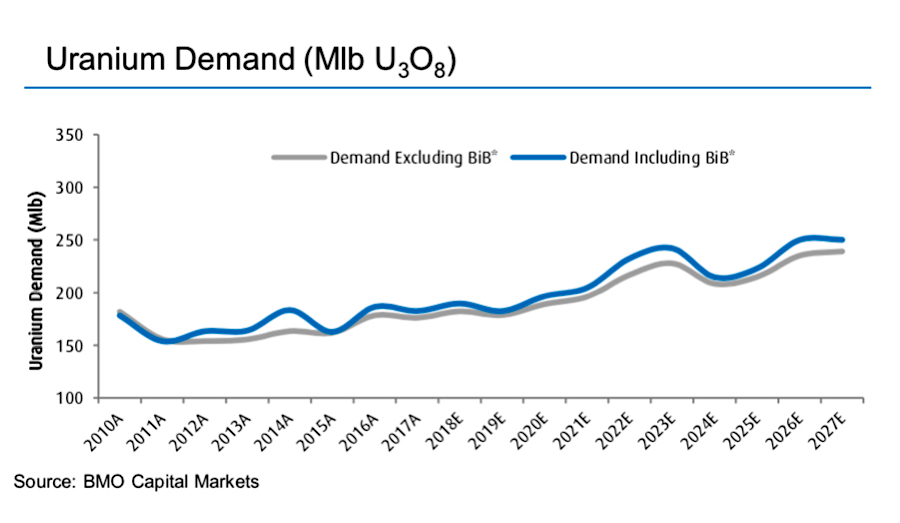

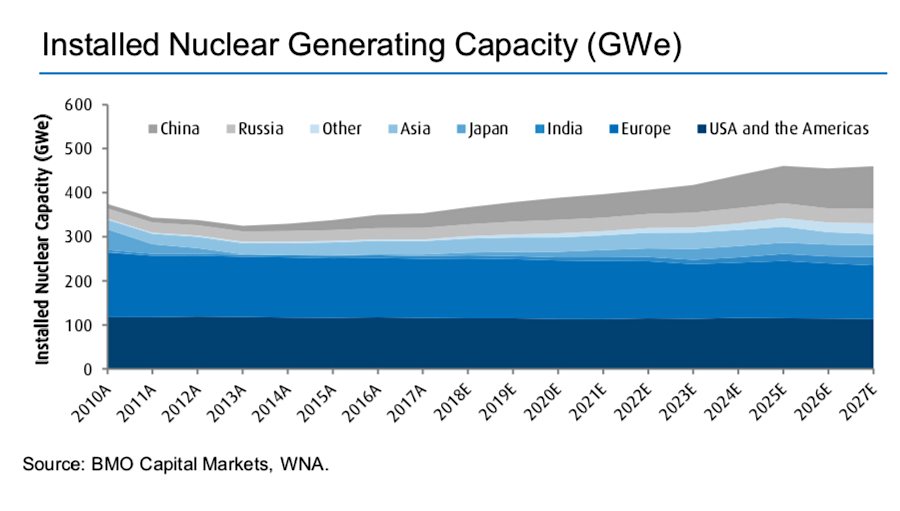

Demand, while still relatively soft, is expected to pick up. There are 55 nuclear reactors currently under construction globally, which will need a steady supply of the metal. China and India, in turn continue to lead that charge as both have aggressive growth policies reliant on nuclear power.

Canada's financial advisor firm Raymond James expects global consumption to increase from about 172 million pounds in 2017 to about 190 million pounds in 2019 and anticipates a supply gap emerging in 2022-2023.

Taken from: BMO's U-Turn: Uranium Thematic Seminar.)

"Given the concentration of production in a few regions (Kazakhstan and Russia now represent over 50% of global primary production), any supply disruptions could lead to meaningful price moves as security of supply concerns return," Raymond James's mining analyst Brian MacArthur told the Northern Miner in August.

The source of uranium supply has changed dramatically over the last decade, creating a situation where security of supply issues could quickly return if supplies to the west from Russia and Kazakhstan were cut off, MacArthur concluded.