Why the End of the Longest Crude Oil Bull Market Since 2008? / Commodities / Crude Oil

In the past two years, crude oil has steadilyadvanced, supported by global recovery. But in just 10 days, oil has posted thelongest losing streak since mid-1984 – thanks to overcapacity and the Trumptrade wars.

In the past two years, crude oil has steadilyadvanced, supported by global recovery. But in just 10 days, oil has posted thelongest losing streak since mid-1984 – thanks to overcapacity and the Trumptrade wars.

Half ayear ago, crude oil prices were expected to climb from $53 per barrel in 2017to $65 per barrel by the year-end and to remain around that level through 2019.By mid-October, crude had soared to $75 and the rise was expected to continue.

Yet, in just10 days oil has fallen to less than $60. Oil prices are in a bear market onemonth after four-year highs. The question is: Why?

Oil’sshort-term fluctuations

The simpleanswer is that until mid-October the escalation of US-Sino trade tensions,despite President Trump’s vocal rhetoric, seemed to be manageable, whichsupported global prospects. Yet, the US mid-term elections have contributed togrowing volatility and uncertainty.

Trump’s illicitdecision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA) contributed to theupward oil trajectory, along with the expected supply disruptions in Venezuelawhich is amid domestic economic turmoil and US efforts at regime change.

AsUS-China tensions continue to linger and bilateral talks have not resulted intangible results, expectations have diminished regarding the anticipatedTrump-Xi meeting in late November. Consequently, global recovery no longer seemsas solid as analysts presumed only recently. Even signs that OPEC and other oilproducers including Russia could soon cut output have not put a floor under themarket.

Also,Trump’s concession, after heavy pressure by Brussels, to allow Iran to remainconnected to SWIFT, which intermediates the bulk of the world’s cross-borderdollar-denominated transactions, has contributed to more subdued oil pricetrajectory.

Anothersupply-side force involves US crude inventories that have been swelling. Thesestockpiles rose by 5.7 million barrels toward the end of October, althoughgasoline and distillate supplies shrunk, according to American PetroleumInstitute. US production is reportedly rising faster than previously projected.

Butwhether these near-term forces will prevail depends on longer-term structuralconditions.

Globalcrisis and post-crisis fluctuations

At the eveof the global financial crisis in summer 2008, crude oil reached an all-timehigh of $145.31. As the bubbles burst, crude plunged to a low of $40; a level itfirst reached at the turn of the ‘80s, amid Iran’s Islamic Revolution.

During theglobal crisis in 2008-9, the US Fed and other central banks in the majoradvanced economies cut the interest rates to zero, while resorting to rounds ofquantitative easing. Meanwhile, policymakers in advanced economies deployedfiscal stimulus packages to re-energize their economies. So, crude rose again untilthe mid-2010s, when the price still hovered above $100 per barrel.

Thattrajectory came to an abrupt end, when the Fed initiated the rate hikes andnormalization policies, which strengthen the US dollar, whereas oil prices,which remain denominated in dollars, took a dramatic plunge. By early 2016,crude prices fell to less than $30 – below the crisis low only eight yearsbefore.

Crudeprices were also hit by the “oil glut”, or surplus crude oil around 2014-15, thanksto critical volumes by the US and Canadian shale oil production, geopoliticalrivalries among oil-producing nations, the eclipse of the “commoditysuper-cycle,” and perceived policy efforts away from fossil fuels. As meetingsby the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) failed to lowerthe ceiling of oil production, the result was a steep oil price meltdown.

Eventually,the 13-member oil cartel was able to agree on a ceiling. At the eve of the OPECtalks in Vienna in spring 2017, oil prices rose to $55. Riyadh needed stabilityto cope with domestic economic challenges and the war against Yemen. So itpermitted Iran to freeze output at pre-sanctions levels. Russia supported thecuts because it remains dependent on oil revenues. The extension also benefitedshale and gas producers in the US and the Americas.

Crudeprices began to climb, but thanks to the OPEC agreement to cut production.

Oil’slonger-term structural prospects

Crudemarkets are under secular transformation. Bargaining power has shifted fromadvanced economies to emerging nations. US is producing record levels of shale.Renewables are capturing more space. Due to sluggish demand, further cuts loomin horizon as prices remain subdued.

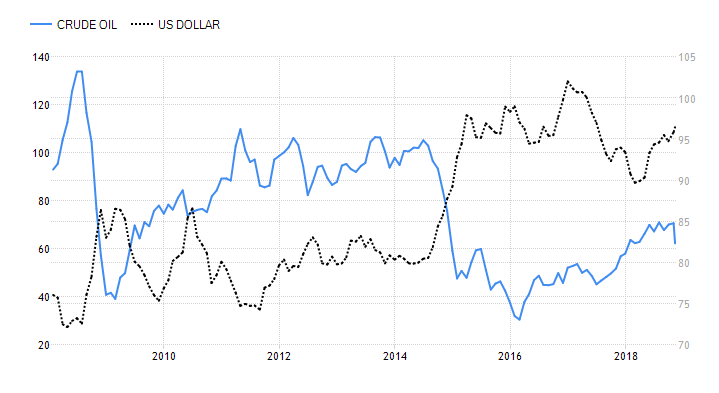

Moreover,when dollar goes up, oil tends to come down. Oil is denominated in US dollars, whosestrength is intertwined with the Fed’s policy rate. As long as the Fed willcontinue to hike rates, this will contribute to further turbulence,particularly in emerging economies amid energy-intensive economic development (Figure).

Figure How US Dollar Undermined Crude Gains,2008-2018

InNovember 2017, OPEC agreed to extend oil supply cuts until the end of 2018. Thatfueled crude from low-$50s in spring 2017 to more than $70 last mid-October. Ineffect, crude mirrored the elusive global recovery, along with the primeindicators of global economic integration.

It wasthese positive horizons of world trade, investment and finance that contributedto steady gains of crude prices until mid-October – but then the fragilerecovery crumbled.

WhenPresident Trump showed no inclination toward US-Sino reconciliation, hopesassociated with world trade, investment and finance finally dissipated. And asthe prospects of global recovery turned elusive, crude prices began a steadyfall.

In theshort-term, the status quo could change, but that would require effectivereconciliation in US-Sino friction and the reversal of US sanctions and energypolicies, among other things. In the long-term, significant changes wouldrequire sustained OPEC production ceilings, economic malaise in leadingemerging economies, dramatic reversal in world trade, investment and financeand – most importantly – the end of the dollar-denominated oil regime and thusthe eclipse of US-Saudi military-energy alignment.

Some ofthese changes are not economically viable. Some are desperately neededinternationally. Still others are not likely to materialize without significantconflicts and geopolitical realignments.

Ironically,there was nothing inevitable about the dramatic reversal of oil prices inOctober. It was not based on economics. Rather, it was the effect of overcapacityand the Trump trade wars fueled by hollow dreams of an ‘America First’ 21stcentury.

That’s America’s policy mistake, but globaleconomy will pay the bill.

Dr Steinbock is thefounder of the Difference Group and has served as the research director at theIndia, China, and America Institute (USA) and a visiting fellow at the ShanghaiInstitutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). Formore information, see http://www.differencegroup.net/

© 2018 Copyright DanSteinbock- All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

DanSteinbock Archive |

© 2005-2018 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.